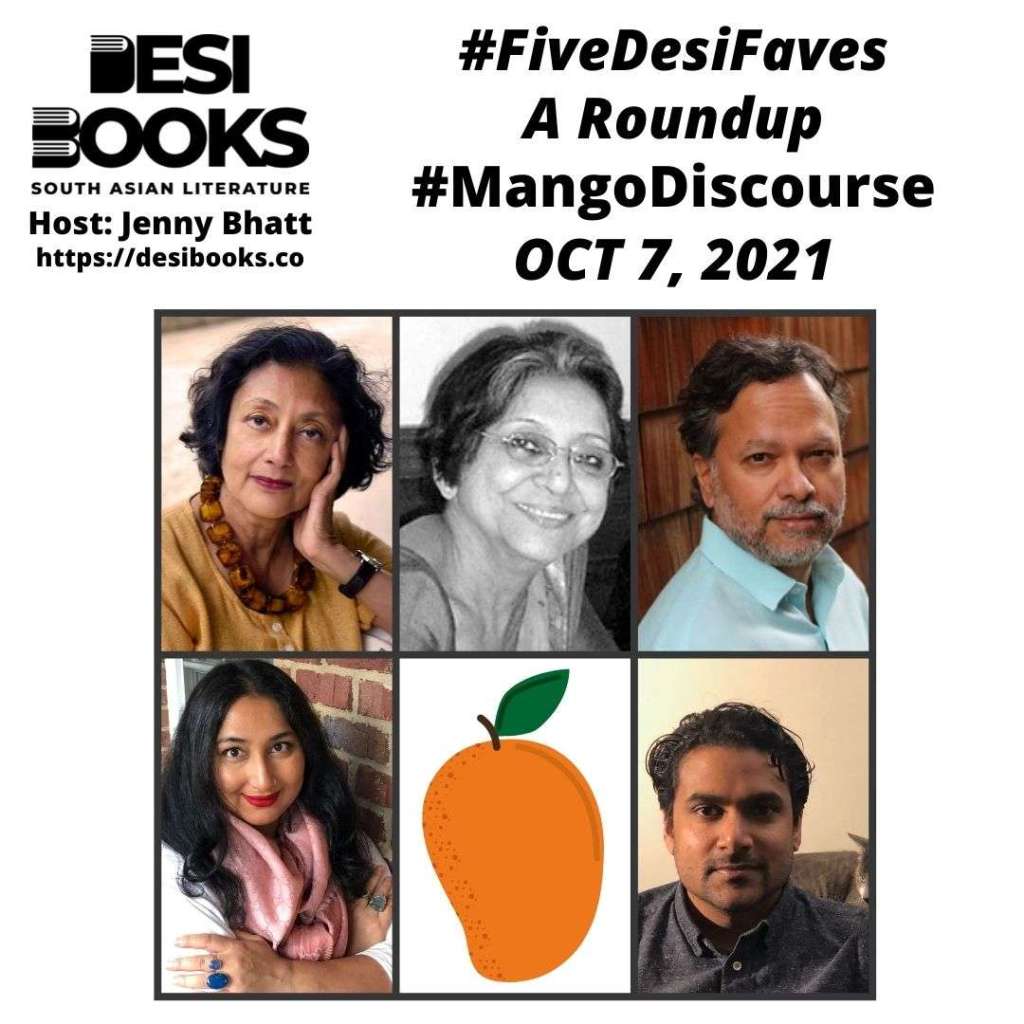

Today’s #FiveDesiFaves is a special roundup of, well, not books. It’s a chronological. though non-exhaustive, listing of all the famous additions to the perennial #mangodiscourse about South Asian fiction. And the five favorites shown above are, if you like, a “hall of fame” set of writers who’ve contributed to this discourse in important ways: Bharati Mukherjee; Meenakshi Mukherjee; Vikram Chandra; Soniah Kamal; Naben Ruthnum.

A #FiveDesiFaves roundup of a “hall of fame” selection of essays on #mangodiscourse by Bharati Mukherjee, Meenakshi Mukherjee, Vikram Chandra, Soniah Kamal, Naben Ruthnum. And several other such essays too. @DesiBooks

Tweet

For definition purposes, #mangodiscourse is about that strong push-pull response we sometimes have when we read a book by a writer of South Asian origin and question its authenticity, fetishization, exoticization, neo-colonialist viewpoint, simplification, etc. These are all loaded terms, of course, and entire Ph.D. theses the world over have been dedicated to unpacking or explaining them.

#mangodiscourse: the strong push-pull response we sometimes have when we read a book by a writer of South Asian origin and question its authenticity, fetishization, exoticization, neo-colonialist viewpoint, simplification, etc. #FiveDesiFaves @DesiBooks

Tweet

South Asian writing in English (let’s call this SAWE versus the much-maligned IWE for Indian writing in English) has had a long and varied tradition starting from the early-19th century colonial era with Henry Louis Vivian Derozio’s Anglo-Indian poetry. Now we’re post-postcolonial, meaning we’ve advanced beyond the limited pantheon of Naipaul, Rushdie, Roy, Ghosh, Lahiri, et al to a thriving and diverse group of writers of SAWE across genres and geographies.

And yet, it is this present-era SAWE that seems to be more problematic than ever. Or, perhaps, academics, critics, writers, and engaged readers are raising their concerns more visibly and vocally than ever. Most of these concerns are pertaining to diasporic SAWE versus homegrown SAWE. (NOTE: The latter is not without its own set of controversies but let’s leave that aside for now.) Many of them have come from diasporic SAWE writers themselves.

Let me add a big, personal DISCLAIMER upfront: I am not taking any particular side in #mangodiscourse though I do have a somewhat different take on it. Long may it thrive and grow because, whether we agree or disagree or dismiss or applaud, discourse can improve our understanding of, engagement with, and approach to this thorny, long-standing issue. I share these so we may all understand, as a community and as individuals, the many historical contours of #mangodiscourse and decide where we prefer to stand.

In a 1988 New York Times Book Review essay, Bharati Mukherjee wrote about South Asian immigrant writing and exhorted younger versions of herself (“Asia-born and United States-raised writers now in their 20s who probably couldn’t wear a sari or other native dress even if begged to do so”) to write about their American scene rather than about an India they barely knew but were “seduced by what others term exotic.”

In 1993, Meenakshi Mukherjee, though not a diasporic writer, famously chided SAWE (well, mostly, Indian but her arguments apply to all South Asian) writers for homogenizing realities and essentializing the region through “a certain flattening out of the complicated and conflicting contours”, along with many other such predilections, so they could present themselves as “real” Indians. She called this “the anxiety of Indianness.” It’s a landmark essay that ignited the SAWE literary landscape then. This was before social media or we’d have seen much more of a public response.

Flash forward to 2000, when Vikram Chandra countered Meenakshi Mukherjee by challenging the many mysterious and arbitrary tests of Indianness and interrogations of authenticity, coining his own term, “the cult of authenticity”, and advising writers like him to not worry about being attacked “for being not Indian enough, for being too Indian, too Westernized, too exoticized, too rich, for being a foreigner, an agent of the CIA.”

Shortly thereafter, Amit Chaudhuri added tangentially to this discourse by wondering, as the editor of the 2004 The Vintage Book of Modern Indian Literature, “Can it be true that Indian writing, that endlessly rich, complex and problematic entity, is to be represented by a handful of writers who write in English, who live in England or America and whom one might have met at a party?” (a direct response to Salman Rushdie’s gushing praise of Indian literature in English in the anthology that he had edited: Mirrorwork: 50 Years of Indian Writing 1947-1997.)

In the early 2000s, Sheetal Majithia called out South Asian American writers for their fetishization of the immigrant narrative to reduce it into easy-to-consume representations.

Almost a decade later, Mohsin Hamid, Mohammed Hanif, Daniyal Mueenuddin, and Kamila Shamsie had fun in 2010 telling diasporic writers how to write about Pakistan (almost all of it applies to the rest of South Asia as well.)

Then came Jeet Thayil with his earnest 2012 avowal to never write about India’s mangoes, spices, and monsoons.

In the now-infamous 2013 New York Times interview, Jhumpa Lahiri tried, in her own way, to push back on the persistence of the “immigrant literature” label slapped onto her body of work. “Immigrant literature” is really a part of #mangodiscourse and the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably these days, I’ve found.

Amitava Kumar valiantly presented his manifesto for Indian literature in English (ILE) (paywall) in 2014 as literature that engages with the “real” by writing stories about India that weren’t intended for export but written for readers in India. He stayed away from the usual trigger words and phrases but he was definitely adding to #mangodiscourse. (NOTE: You may not be able to read the entire essay from behind the paywall but my little 2014 comment at the very bottom is still there.)

Jabeen Akhtar added to the authenticity debate in 2014 with her catalog of 17 specific elements of the bad South Asian novel and how it’s really all about pandering to Western audiences.

In 2016, Soniah Kamal made a terrific declaration about taking back her right to include mangoes, monsoons, spices, monkeys, peacocks, snakes, mynahs, bangles, bindis, saris, sequins, buffaloes, paranthas, anklets, tangas, burqas, hijabs, samosas, arranged marriage, and love marriage.

The next well-known addition to this never-ending discourse was from Naben Ruthnum in 2017 about how the demand for authenticity means that diasporic writers have to play both tourist and tour guide resulting in “false stories, or stories with false elements burying truthful details and experience, built on conventions created by other writers and the categorizations of the publishing industry.”

In 2020, I gave various interviews about writing beyond mangoes, saris, slums, etc. with my own debut story collection, Each of Us Killers, which focuses on Indians in their workplaces in India, the US, and the UK.

Urvi Khumbhat jumped into the “mango discourse” in 2021 with a personal genealogy of her own as she discussed diasporic literature.

Oh, and let’s not forget Sanjena Sathian’s fiery 2021 attack on poor Jhumpa Lahiri and all the problems with “good immigrant novels.” (Personal note: I applauded her bravery and even agreed with some, though not all, of the points when the essay was published. But I have the impression that Sathian would probably write a slightly different essay in hindsight. I hope so.)

Most recently, even the great Salman Rushdie weighed in, forty years after Midnight’s Children, with this: “Writing my book in North London, looking out through my window on to a city scene totally unlike the ones I was imagining on to paper, I was constantly plagued by this problem, until I felt obliged to face it in the text, to make clear that […] what I was actually doing was a novel of memory and about memory, so that my India was just that: “my” India, a version and no more than one version of all the hundreds of millions of possible versions.”

Actually, the most thought-provoking additions to #mangodiscourse have probably been from book critics, all of which would make for a much longer and more controversial chronology than we have space or time for now. A brief sampling, then.

- This 2011 review by Sarfraz Manzoor of the British anthology, Too Asian, Not Asian Enough (edited by Kavita Bhanot), said the book failed to leave the “familiar tropes and tired clichés” behind.

- A 2012 review of Jeet Thayil’s Narcopolis by Kevin Rushby talked about “. . . any books by foreign-educated Indians read as though they were written in a New York penthouse suite, the author having spent a couple of weeks researching a multi-generational, sprawling saga of Mumbai lowlife by chatting to the house servants of their relatives on the phone.”

- And this 2008 clapback by the inimitable Jeet Thayil to another book critic was for being patronizing and reductionist in expecting the same old, same old from South Asian writing.

- Parul Sehgal had problems with Arundhati Roy’s “lack of psychological shading” and more in 2017 (although, interestingly, she did not find any such concerns, which other critics have pointed out, with another book in 2020.)

- Sehgal was also not happy with Preti Taneja’s debut novel for many reasons that are directly or tangentially related to #mangodiscourse.

- More recently, book critics (especially in India) were divided about Megha Majumdar’s 2020 debut novel, calling it “an attenuated version of the complex, violent remaking of India” (Amrita Datta) and saying that it “lacks the depth of cultural experience of what it means to be projected as a Muslim terrorist” (Irfan Ahmed.)

Let me stop there before the entire South Asian literati comes after me. And, for self-preservation, I’ll repeat my disclaimer from above: I am not taking any particular side in #mangodiscourse. Long may it thrive and grow because, whether we agree or disagree or dismiss or applaud, discourse can improve our understanding of, engagement with, and approach to this thorny, long-standing issue.

Please do point me to any essays I may be missing and I will gladly add them here. Thank you.

~Jenny Bhatt, Founder and Editor-in-Chief, Desi Books

A #FiveDesiFaves roundup of a “hall of fame” selection of essays on #mangodiscourse by Bharati Mukherjee, Meenakshi Mukherjee, Vikram Chandra, Soniah Kamal, Naben Ruthnum. And several other such essays too. @DesiBooks

Tweet

Join the Conversation